Introduction

Ikko Ohno and his film The Flying Luna Clipper occupy an unusual spot in the history of video games, animation, the cross-pollination of games and cinema, gaming technology, and digital art. Made in its entirety with a MSX microcomputer in 1987, it probably remains the sole entry of what we have called elsewhere “chipcinema," that is, films made with early gaming technology.1 The Flying Luna Clipper also predated machinima and paralleled the rise of the so-called demoscene, “a type of computer art that has emerged in the 1980s and 90s in Europe” that appeared “at the intersection of the creative computing domains of: creative programming, video game development, electronic music, new media art and computer animation.”2 The Flying Luna Clipper was far more ambitious than demos: it had characters, voice acting, and a narrative arc (no matter how odd). Its length, fifty-five minutes, qualifies it as a feature film according to the criteria of institutions like the BFI, the AFI Catalog, and the Academy Awards.3 Way before James “Jimmy ScreamerClauz” Creamer made Where the Dead Go to Die (2012) and When Black Birds Fly (2016) all by himself using Maya, or Gints Zilbalodis likewise did with Away (2019), Ohno’s The Flying Luna Clipper was, to our knowledge, the first commercially distributed feature film made fully with gaming technology by a single author. And although the past decade has seen some entries into that improbable and highly specific category, the value of The Flying Luna Clipper lies not only in being a pioneer (it was made during the early days of computer-generated graphics [CG] and way before machinima), but in being an exception.

Too often history and its writing are highly focused on genealogies, patterns, and clear lines, reducing a medium to a chain of continuities, evolutions, and mutations. Exploring The Flying Luna Clipper forces us to look at history in a different manner: as a space of rarities and dead ends, of trends that could have been and were not. There is nothing quite like it, and yet its aesthetic is familiar to many veteran players. Its plot, about a group of dreamers (including a snowman and anthropomorphic fruits) who embark on the inaugural flight of a seaplane (the eponymous Flying Luna Clipper) across the Pacific, would not be out of place in a 1980s Japanese video game. The pixel art, the crude animations, the digitized voices: watching it, those familiar with the MSX can undoubtedly identify the platform and its affordances. The Flying Luna Clipper is a good demonstration of what that microcomputer could do, and as such, we argue, it should be included in any history of the platform. From a platform studies perspective,4 the film illustrates the system’s capabilities in a unique way: by focusing on its noninteractive aspects. The MSX is by no means a minor platform (a concept explored, for instance, by Benjamin Nicoll and Carl Therrien),5 but studying it as a movie-making platform helps us cross the “epistemic threshold” of platform studies.6 Last, let’s not forget that The Flying Luna Clipper was released the same year that Maniac Mansion (1987) reached the market, cementing the idea of cut scenes in the minds of players and developers alike. Considering The Flying Luna Clipper not only as a movie but as a collection of cinematics shows how advanced and clever it was at the time and places it more firmly in the history of games.

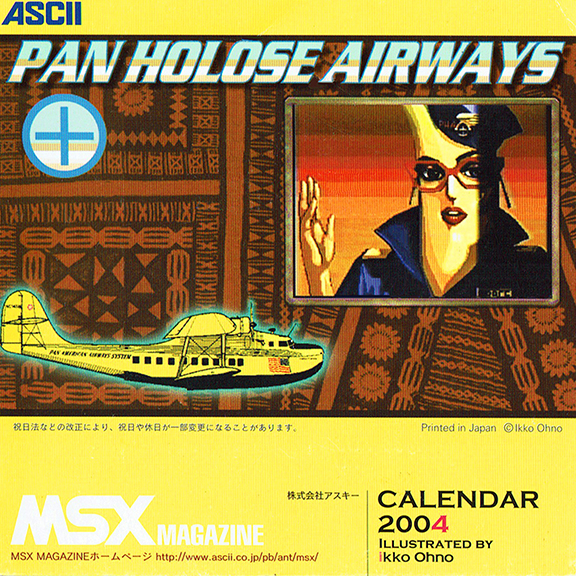

This is why we have interviewed Ohno himself to discuss the film and its creation process and context. To properly introduce the interview, we must present a timeline of how we discovered The Flying Luna Clipper and how it has started to have a small cult following in Western countries. The movie was virtually unknown outside Japan before 2015 and probably barely remembered there until then. At that time, game critic Matt Hawkins published two posts (on December 10 and December 11) on his blog Attracta Mode,7 where he introduced the film and reviewed it. It was found, according to Hawkins, as a LaserDisc in a thrift shop by someone “who shall remain anonymous.” The full movie was uploaded at the time to Attracta Mode’s YouTube channel (at the moment of writing, it has 24,219 views).8 In his first post, Hawkins wrote that “virtually no information exists online” and that The Flying Luna Clipper was “the brainchild of Ikko Ono [sic], who again I’m completely clueless about.” On March 28, 2017, Víctor Navarro-Remesal wrote about it for the now defunct online cultural magazine O. Twitter user @ImanokMSX replied shortly after that explaining that “years ago, I participated in a contest of @msxorg and won a calendar where these characters appeared” and produced photos of it. The desk calendar was for 2004 and it was clearly set in the world of The Flying Luna Clipper. That fit with something Hawkins had written: “Supposedly a sequel was produced in 2004 and is equally shrouded in mystery.” A month later, the movie was added to some MSX fan sites, such as MSX.org, but still nobody could find any information about it.9

This is when Marçal Mora-Cantallops was able to find and contact Ohno, a still active graphic designer from Kochi based in Setagaya, Tokyo. Born in 1950 and an alumnus of Musashino Art University (Faculty of Art and Design), Ohno was thirty-seven years old and fully established as a professional when he made The Flying Luna Clipper. He gently answered all of our questions (we interacted in Japanese with the help of Mika Taga and Tatsuya Oda) and shared a plethora of materials with us. With the information we obtained, Navarro-Remesal was able to include a chapter on The Flying Luna Clipper in his book Cine Ludens: 50 diálogos entre el juego y el cine, in which he explored play through film and the intertextualities and exchanges between movies and games. We discovered that “Ikko’s Theatre,” a title shown in the movie, was the name of a section Ohno had in MSX Magazine in the late 1980s, where he promoted the microcomputer as an accessible tool for graphic design, and that The Flying Luna Clipper was put together from episodes published with that magazine at the request of Sony, who needed to promote LaserDisc as a format.

By 2019, The Flying Luna Clipper was gaining traction among some sectors of the internet. Hawkins continued researching the film and promoting it, screening it (probably for the first time outside Japan) on August 28 at Wonderville, a Brooklyn (NYC) bar, arcade, and event space. One year later, on August 30, 2020, Hawkins screened it again, this time on Wonderville’s Twitch channel. For this new screening, and having talked to Navarro-Remesal about Ohno and our interview, Hawkins contacted Ohno himself and asked for his blessing—which Ohno granted, along with a lot of new material, including original storyboards. That very month, Hawkins created a new post in Attracta Mode’s new Medium blog, entitled “Dream Flight Interpreted: The Deconstructed Flying Luna Clipper,” where he gathered everything he had on the film and has been updating since (the last update was on September 11, 2020).10 Moreover, our combined research seems to have motivated Ohno to track old materials and discuss the film on his Facebook account, and many people have begun noticing The Flying Luna Clipper, especially fans of retrogaming, the MSX, and film rarities. The cult of The Flying Luna Clipper lives on.

This is what motivated us to go back to our original interview, contact Ohno again to add further questions, and return to the many files he sent us (we have communicated with him via email and Facebook Messenger). Throughout this whole process, The Flying Luna Clipper has remained a fascinating oddity, a beacon of a half-forgotten moment in the history of a vital platform for early Japanese gaming. We hope this interview helps The Flying Luna Clipper and its creator, Ikko Ohno, get the recognition they deserve.11

Figure 1

Interview

Victor Navarro-Remesal, Marçal Mora, Yoshihiro Hino: Hello, Mr. Ohno. We are very happy to talk to you about The Flying Luna Clipper and the MSX.

Ikko Ohno: This was happy news. I have to put my memories in order, so my answers can be long and off-topic, but I will answer your questions gladly. I must warn you that my Japanese is very personal and hard to understand, especially the one I used for my articles for MSX Magazine. Please, ask me if there’s something you don’t understand.

VNR, MM, YH: How did the idea for The Flying Luna Clipper originate?

IO: It is actually a collection, an omnibus, of short movie clips made with a MSX microcomputer and its graphic software. They were made for the MSX magazine, as part of a series entitled “Ikko’s Theatre.” The idea of that “theatre” came from several concepts such as: (1) Virtual theaters that would be used for the screening of my works; (2) Open theaters at overseas resorts or unexplored regions with superb views; (3) Tahiti—where I visited to look for filming locations.

VNR, MM, YH: What was your professional and artistic experience before that movie?

IO: After I graduated from Musashino Art University in 1973, I specialized in drawing realistic illustrations using an airbrush, as a freelance illustrator. In 1980, I planned a TV commercial for KITZ, in Japan, and I drew the storyboard with an airbrush. It was common to use wire frame CG, but the commercial was made by advanced solid frame CG. That commercial was made in CG, and the solid frame for it was planned at Digital Effects, a studio in New York that was involved in Disney’s Tron.12 Also in 1980, I planned and designed a TV title at JCGL [Japan Computer Graphics Lab]. This was Japan’s first CG production. In 1981, I drew three cover illustrations for the Japanese computer magazine monthly ASCII at Digital Effects, sending rough sketches by telex.13

Figure 2

Cover for the magazine ASCII created by Mr. Ohno. (Image courtesy of Ikko Ohno)

VNR, MM, YH: And then, from what we see in the materials you sent us, you made more covers after that.

IO: In parallel to the production of these CG works, I developed a friendship with ASCII founder Kazuhiko Nishi. I was interested in developing 2-D CG with a pen tablet. In 1984, I was asked to produce an illustration for the cover of the May issue of MSX Magazine and for that I was provided with an MSX and the proper equipment.14 I tried to draw a cover picture with the machine, but gave up because of its limitations. The drawing software had a resolution of 256 by 192 pixels and 16 fixed colors. In addition, color interferences occurred in units of 16 by 16 pixels, causing block noise.

VNR, MM, YH: Your first attempt at using an MSX for art failed.

IO: I ended up doing the cover illustration with a NEC PC-100 computer I already had. It had a resolution of 512 by 720 pixels, with 16 simultaneous colors from a total of 512 colors. By coincidence, the NEC PC-100 was also born from an idea by Mr. Nishi. I did that cover with a computer mouse that was used for the first time in Japan. I took a picture of the screen with a Hasselblad camera (6-centimeters-square film) and delivered it to a printing office, then I continued doing it that way until the cover of July 1985. Kazuhiko Nishi, by then vice president of ASCII, saw it and asked me, “why don’t you draw with the MSX?” I told him the reason and he said “I’ll adjust the machine specs so it can support Ohno-san’s use.”

VNR, MM, YH: How was your experience with MSX Magazine?

IO: I was lucky enough to explore the possibilities of computer graphics in its early period. However, I felt it was unfair that those of us involved in CG monopolized the technique. I was impressed by the idea of Mr. Nishi of achieving an information revolution with personal computers that were affordable and accessible for children. In an essay for MSX Magazine, I compared the graphic functions and capabilities of models created by thirteen different manufacturers, understanding them as expressive tools for pictures and video. I highlighted these three benefits: (1) promoting ASCII and the thirteen manufacturers through the popularization of the MSX microcomputer, (2) developing young talents using the MSX as a home electronic appliance to program and create texts and audiovisual materials, (3) evolving my own creation tools for digital picture and video production.15

Figure 3

MSX Magazine , November 1985. (Image courtesy of Ikko Ohno)

Figure 4

Final pages of the section “Kimi mo illustrator.” The feature was signed by Mr. Ohno, indicating an authorial position close to the reader. (Image courtesy of Ikko Ohno)

VNR, MM, YH: What did you exactly do for the magazine?

IO: In addition to covers, I was in charge of a feature entitled “Kimi mo illustrator” (You are an illustrator), from July 1984 to July 1985. Then I published illustrations and essays in “Ikko’s Gallery” from April 1986 to December 1986. “Ikko’s Theatre” had 4 pages per month. I regarded it as a virtual theater that screened experimental motion video. I introduced primitive animations from January 1987 to December 1987.

VNR, MM, YH: How did you find drawing with the MSX?

IO: The MSX is an 8-bit machine with two planes. I made the animations using these two frames. On the first plane, I drew a scene and indicated a location to animate on a surface of a square. On the second plane, I made an animation frame rewriting slowly the part that was moving, dividing the square into some pieces. I also made a program that played the animation frame on repeat using MS-DOS. That program could continue to play these two planes in loop.

VNR, MM, YH: Did you use any other tool than the MSX?

IO: I recorded the animations made with the MSX on a one-inch video recorder offered by Sony, converting digital signals to analog. I added picture compositions and special effects using Digital Video Effect at a video editing room in the Minami-Aoyama Spiral Hall that opened in 1983 in Tokyo.

VNR, MM, YH: There’s a live-action sequence, “Gravity Dance,” in the middle of the film, although it seems processed by a MSX as well. Why did you introduce that part?

IO: The basic concept of the movie was an omnibus, as I explained previously, so I decided to insert a part of the productions I had made earlier for the video promotional office at Sony. I am sending you an article for the newspaper Eizo Shimbun and a piece in the August 1986 issue of MSX Magazine entitled “Why Sony?” where you’ll find more about this.16

Figure 5

Article for the trade paper Eizo Shimbun on the MSX’s proven record for video production. Ikko’s Theatre The Frying [ sic ] Luna Clipper illustrates it. (Image courtesy of Ikko Ohno)

Figure 6

An article on “Gravity Dance” was included in the August 1986 issue of MSX Magazine . (Image courtesy of Ikko Ohno)

Figure 7

Mr. Ohno at the TV show Sports USA . (Image courtesy Ikko Ohno)

VNR, MM, YH: In the credits and on the internet, you appear as the film’s director. Did you do anything else?

IO: I was in charge of everything. I was the producer, the director, I was the creator of the drawings, the scripts, the background designs, the art, sounds, editing.

VNR, MM, YH: Was anyone else involved?

IO: I was running a video production company called C-STAFF Co., Ltd., with two of my juniors. We assigned tasks such as animating MSX data of original pictures, backgrounds, characters, and so on based on storyboards and scripts. Mr. Fumitaka Anzai (ANZ) composed music for my work using analogue synthesizers like the Fairlight Computer Musical Instrument [CMI]. He was familiar with the Fairlight CMI because of his score for the adaptation of the manga Urusei Yatsura.17

VNR, MM, YH: The Flying Luna Clipper was more of a personal project.

IO: Regarding the digital tools used for 3-D CG in its early days, I was not satisfied with the difficulties in communication within a large group, and with how budgets were too big to handle. I was originally just an illustrator who completed all the tasks by myself. Then, as an extension of that, it was easy to jump to “making fixed images move” with the MSX as an expression tool.

VNR, MM, YH: When was it released and why on LaserDisc?

IO: It was released on October 1, 1987. The promotion division of Sony paid the production costs of the LaserDisc because Sony wanted to make the format known. I had worked with them before. MSX Magazine was selling 100,000 copies every month by that point and Sony offered to publish “the collected works of Ikko Ohno with the MSX” for those enthusiast fans as their main target.

VNR, MM, YH: All the dialogue in the movie is spoken in English, instead of Japanese. Can we ask why?

IO: The MSX market was not only in Japan, but overseas. Also, I personally have fond memories of the Hollywood movies I watched as a child, of their different culture and dream world. As an audience, I wanted to immerse myself in those memories. Finally, while I was in Tahiti location scouting, my wife informed me that she was pregnant. My wife was traveling in San Diego at that time. I got a strong motivation to work for the baby that we expected. The release date was supposed to be the birthday of my first child. I wanted to raise my child in an international environment.

VNR, MM, YH: Who did you cast as voice actors?

IO: No one particularly famous, really. I chose voice actors through an audition. This project was financially supported by Sony, as I said, but the budget was not enough so I had to reduce costs. I also believed that a famous voice actor would not be ideal for the freshness of the characters I had in mind.

VNR, MM, YH: Let’s talk about themes and inspirations. You’ve mentioned an international environment. Why use anthropomorphic animals and vegetables for the main characters?

IO: I used characters like that regularly. I was creating them between July 1981 and April 1986 for my covers and illustrations. Vegetables and fruits appeared on the covers I made for Big Comic Spirits, a weekly magazine published by the publishing house Shogakukan with a distribution of one million copies per week. They’re my original characters. Since the magazine was so well-known and its cover had such an impact on readers, I used them hoping they would be good for marketing. I designed various vegetables and fruits but the most frequently used one was a banana, which I also liked very much.

Figure 8

Some of the covers Mr. Ohno created for MSX Magazine . (Image courtesy of Ikko Ohno)

VNR, MM, YH: Travel, as a theme, is very central in the movie.

IO: It is a pleasure traveling to strange lands I don’t know. I also was a member of the Japan Travel Writers’ Organization at the time. In those days I was especially interested in exploring the Polynesian culture and its islands, which covers indigenous people from the Maori of New Zealand to Hawaii.

VNR, MM, YH: What about the sentence “everything is true in your dream”?

IO: With that I meant “everything is true in your dream” through “programming the future = drawing a dream,” a message especially aimed at junior and senior high school students, which were the majority of readers of MSX Magazine.18

VNR, MM, YH: And where did the idea of the Flying Luna Clipper, the seaplane, came from?

IO: First, I was inspired by two Beatles movies, Magical Mystery Tour (1967) and Yellow Submarine (1968). In the first one, an unprecedented number of passengers get on a bus and a music clip is inserted in the middle of the film. This is a new style, before MTV and music videos. Yellow Submarine influenced me because it was not only entertainment: it mixed psychedelics, surrealism, and its concept had a very artistic approach to pop art that I found stimulating. I designed a yellow flying boat thinking of a road movie like Yellow Submarine. It was a flying boat because I like aircrafts and was inspired by a book, one of a documentary novel series of which I illustrated front covers. It was called Kieta Hikousen (The Missing Flying Boat)—a documentary novel published by the Mainichi Shimbun newspaper company in 1976. This book covers the history of three aircrafts that mysteriously disappeared. Before World War II, in November 1935, a new flight route opened between San Francisco and Manila via Honolulu, Midway Atoll, Wake Island, and Guam. Three planes of the Martin M-130 model were built. They were called China Clipper, Hawaii Clipper, and Philippines Clipper. The three flew this route and all of them disappeared. I don’t have a copy of this book, but have a proof sheet of the front page. Please see it in the attachments.

Figure 9

The book cover created by Mr. Ohno for Kieta Hikousen . (Image courtesy of Ikko Ohno)

VNR, MM, YH: Is this why you chose the Pacific as the setting?

IO: I was born and raised in the Kochi Prefecture, in the southeast of Japan, facing the Pacific Ocean. Nature is rich there and the weather is warm. I have these landscapes in my heart: steep mountains, summer clouds, rainbows, rainfalls, and the sea. Also, in 1963 I watched the film Tiko and the Shark (1962). I was thirteen years old and it made a big impression on me. It made me have a big longing for Tahiti. In 1980, I visited Tahiti (Moorea and Bora Bora islands) for my honeymoon. During my fifteen-day stay, I spent a dreamy time watching the beautiful sea horizon and the sunset over the shadows of the mountains. It stole my heart. It was like crossing my visual memories and realities. I had a happy moment watching a vaguely ghostly story.

VNR, MM, YH: Tahiti became a recurrent motif.

IO: In 1986, I drew a scene of waterfalls based on my memories of Tahiti at an installation called Jungle Choir displaying six MSX machines. In March 1987, Sony asked me to make content for their LaserDisc format, as I explained before, and I immediately decided to make a story about Tahiti. I read the historical facts of the missing aircrafts, ready to replace them with a fantasy version. Then, I chose a city called Saint Petersburg, Florida, as the spot where the Martin M-130 of mystery and legend would be discovered. In March 1987, I revisited Tahiti for location scouting. In October of that same year, my son was born. I actually wanted a son and intended to design a male character for The Flying Luna Clipper, but I had learned the lesson from Buddha that one should not expect to get what one wants, so I designed a girly character, a flower called Tiara. In April 1990, I finally visited Saint Petersburg, Florida. Many years after the movie, in August 1991, I revisited Tahiti for the third time, now with my son.

Figure 10

Article in Epsilon (computer music and visuals magazine) with full details on the making of The Flying Luna Clipper . (Image courtesy of Ikko Ohno)

VNR, MM, YH: What about Honolulu? Did you visit it for references too?

IO: In 1980, for my honeymoon, it took forty-eight hours to fly from Tokyo to Papeete, in Tahiti, changing planes at Nouméa, New Caledonia. But when I went location scouting years later, in 1987, I could go from Tokyo to Papeete via Honolulu, in Hawaii. Taking the opportunity of the transit at Honolulu on my way back, I visited the Polynesian Cultural Center at Laie for an interview. I watched a fantastic Tahitian show in the evening. The Tahitian show at the end of The Flying Luna Clipper came from my experience there, from a night show they had. I also collected data about double canoes from the Polynesian Cultural Center and the Bishop Museum (Honolulu) for the canoe scene in The Flying Luna Clipper.

Figure 11

The Flying Luna Clipper 2004, a calendar with new scenes created by Mr. Ohno. (Image courtesy of Ikko Ohno)

VNR, MM, YH: We’ve seen a calendar for 2004 with the MSX Magazine logo and the characters from the movie. Was there ever a plan for The Flying Luna Clipper 2?

IO: I am always interested in doing something new and not going back to things I’ve already done, so I never thought about The Flying Luna Clipper 2. In 2003 the MSX Magazine had a revival, and I made an illustration for the cover of its second limited edition [Eikyuu Hozon Ban 2], published in December 2003.19 I used an MSX2 to create the picture of a snowman and a banana. At that time, I also had an interview with the chief editor of the magazine. This is when I made “The Flying Luna Clipper 2004” as a set of twelve scenes presented with twelve illustrations, and a simple text for the episode with the banana and the snowman meeting fifteen years later. Later, I published a small calendar, the size of a CD, with these twelve illustrations. Some fans requested me to make The Flying Luna Clipper 2 at a publication event Q&A. Although I thought it was an interesting idea, and I was moved by that request, I did not make it, unfortunately.

Figure 12

Mr. Ohno’s cover for the revival of MSX Magazine in 2003. (Image courtesy of Ikko Ohno)

VNR, MM, YH: We haven’t talked about video games yet. Do you play? And what do you think of the MSX as a gaming machine?

IO: I do not play video games, so I do not have any particular opinions about the MSX as a gaming machine. I want to draw my favorite world, a world that does not exist anywhere, and stay there comfortably.

VNR, MM, YH: Can we ask you about your thoughts on machinima?

IO: When Second Life, produced by Linden Lab in San Francisco, became popular around 2004 and 2005, I thought it was interesting. But, it did not have enough expressivity and operability, so I did not use it, my interest waned. It might be more interesting in today’s developed digital environment, although I have not used Unity yet.

VNR, MM, YH: Can you tell us a bit about your professional experience in other fields, such as personal computers, video games, and movies?

IO: I have not been good at playing video games since I worked with the MSX, therefore I have not worked for video games. I wrote scripts and illustrations for an original movie titled Mari to koinu no monogatari (A Tale of Mari and Three Puppies, 2007). It was a very lonely but happy job making forty minutes of Flash animation by myself.20

VNR, MM, YH: Did you imagine that people would be asking about The Flying Luna Clipper thirty years later from other parts of the world?

IO: I never even thought I would be alive thirty years later. I am very happy that young people come to ask me about my experiences.

VNR, MM, YH: On a closing note, what do you think makes pixel art and video game graphics special for an artist like yourself?

IO: Pixel art is one means in graphic arts among others. For me, who was drawing 2-D illustrations with an airbrush at the early days of CG, the MSX was useful because it was an affordable tool, like a paintbrush. It was simple like a pencil. To make animations in large numbers, pixel art is very convenient for keeping things manageable and working alone. I had to prepare many original drawings by myself. So, the limited resolutions and colors of the MSX helped me draw pixel art paradoxically without spending an enormous amount of time and effort. I believe that pixel art has an intrinsic value as a style of expression for its symbolic nature. There is a margin that is omitted and the viewer has to imagine. It allows viewers to imagine things for themselves in the space they see. In this, parallel Japanese forms of expression like, for example, haiku, or aesthetic sensibilities like wabi-sabi, which are somewhat related to that capacity for imagination in the margins. Pixel art allows us to express a view on the world through omission and imagination.

VNR, MM, YH: Thank you for your time and patience, Mr. Ohno.

Figure 13

Some pages of The Flying Luna Clipper script and storyboard. (Image courtesy of Ikko Ohno)

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Ikko Ohno, Mika Taga, and Tatsuya Oda for their help with the first contact and interview, and Matt Hawkins for making the film public and curating it over the years.

Footnotes

1. ^ Victor Navarro-Remesal, Cine Ludens: 50 diálogos entre el juego y el cine (Barcelona: Editorial UOC, 2019).

2. ^ Maria Garda, “Impact Story: Recognizing the Demoscene as Digital Cultural Heritage,” Centre of Excellence in Game Culture Studies, February 9, 2021, https://coe-gamecult.org/2021/02/09/impact-story-recognizing-the-demoscene-as-digital-cultural-heritage/.

3. ^ “BFI Filmography Project Overview,” BFI, accessed February 1, 2021, https://www.bfi.org.uk/bfi-national-archive/research-bfi-archive/bfi-filmography/bfi-filmography-project-overview.

4. ^ Nick Montfort and Ian Bogost, Racing the Beam: The Atari Video Computer System (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2009).

5. ^ Benjamin Nicoll, Minor Platforms in Videogame History (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2019); and Carl Therrien, The Media Snatcher: PC/CORE/TURBO/ENGINE/GRAFX/16/CDROM2/SUPER/DUO/ARCADE/RX (Cambridge: MA: MIT Press, 2019).

6. ^ Tom Apperley and Jussi Parikka, “Platform Studies’ Epistemic Threshold,” Games and Culture 13, no. 4 (2018): 349–69.

7. ^ Matt Hawkins, “Review: The Flying Luna Clipper, Part 1,” Attracta Mode (blog), December 10, 2015, https://blog.attractmo.de/post/134913165050/review-the-flying-luna-clipper-part-1-my-love; and Matt Hawkins, “Review: The Flying Luna Clipper, Part 2,” Attracta Mode (blog), December 11, 2015, https://blog.attractmo.de/post/134976251900/review-the-flying-luna-clipper-part-2-ladies.

8. ^ For the full movie upload at Attracta Mode channel, see Attracta Mode, “The Flying Luna Clipper (Complete),” December 13, 2015, video, 55:33, https://youtu.be/P2TNZyCWA-Q.

9. ^ Pac, “The Flying Luna Clipper Movie,” News, MSX Resource Center, April 7, 2017, https://www.msx.org/news/media/en/the-fliying-luna-clipper-movie.

10. ^ Matt Hawkins, “Dream Flight Interpreted: The Deconstructed Flying Luna Clipper,” Attracta Mode (blog), August 4, 2020, https://medium.com/attract-mode/dream-flight-interpreted-the-possible-flying-luna-clipper-origin-11c1ee5ebe1f.

11. ^ A note on translation: Ohno’s way of writing is very particular and idiosyncratic and can be difficult to understand even for a native Japanese, as he himself acknowledges. The translation we present here is not always literal; while keeping all the facts accurate was our main priority, some rephrasing was needed to convey meaning and for the sake of readability. The original Japanese text is available for consultation if needed.

12. ^ The studio was active from 1978 to 1986 and was the first computer graphics house in New York. They specialized in “flying logos.” See “Digital Effects,” Advanced Computing Center for the Arts and Design, The Ohio State University, accessed February 3, 2021, https://web.archive.org/web/20060623062205/http://accad.osu.edu/~waynec/history/tree/de.html.

13. ^ The ASCII Corporation published ASCII in Japan starting in 1977.

14. ^ MSX Magazine ran from 1983 to 1992 in Japan.

15. ^ The chief editor of MSX Magazine, Mr. Shunichi Taguchi, thought of the MSX as a “home personal computer” and an “intelligence tool.” Therefore, articles in the magazine focused on practical uses of the MSX. He did not want to make it like a more traditional computer magazine and adopted unique illustrations on its front pages. The November 1985 issue of MSX Magazine (fig. 3) contains the feature article “My Own Usage of the MSX,” introducing how Mr. Ohno established a set of machines to create video graphics with the MSX. In MSX Magazine Mr. Ohno’s title was “Digital Performer.” He introduced concrete and practical examples of production methods in the magazine and insisted that the MSX was not only a gaming machine but also a machine with many uses. “MSXは“新庄”だ!?――MSX復活!“MSXマガジンまつり”開催!!,” ASCII.JP, accessed February 4, 2021, https://ascii.jp/elem/000/000/336/336119/.

16. ^ According to the trade paper Eizo Shimbun issued on January 23, 1989, C-STAFF also worked on promotion videos for Music Station—one of the most popular music shows in Japan and Tokyo’s local news program that was broadcast on the leading TV station, TV Asahi. “Ikko’s Theatre” was also broadcast on TV Asahi’s program Sports USA for four months. Mr. Ohno showed his interests in 3-D technology but believed that it was more interesting to pursue his own values by making computer graphics by equipment with lower specification limits. On September 11, 2020, Mr. Ohno reposted a Facebook post with a video showing one of his appearances on Sports USA. In it, he discussed “Gravity Dance.” His new post was due to Hawkins’s new screening of the movie in NYC, and in the text Mr. Ohno explained: “this ‘Gravity Dance’ was produced in 1986 to demonstrate the high definition and color capabilities of the Sony Trinitron TV, at the request of Sony Video Promotion Office’s director, Mr. Kan Tsuzurahara. ... One year later, I was asked if I wanted to release my MSX anime collection under the Sony brand. It became an omnibus.”

17. ^ Mr. Anzai is credited with the score of the TV adaptation of Urusei Yatsura (Fuji TV, 1981–1986), a manga (1978–1987) originally created by popular and respected mangaka Rumiko Takahashi, as well as its movie spin-off Urusei Yatsura (Only You, 1983). He is credited in The Flying Luna Clipper as the original composer.

18. ^ Thirteen to eighteen years old in Japan.

19. ^ This magazine is known among fans as “MSX Magazine—Permanent Preservation Project” or “MSX Magazine 2003.” See Snout, “Two New MSX Magazines,” News, MSX Resource Center, January 18, 2003, https://www.msx.org/news/msx-revival/en/two-new-msx-magazines.

20. ^ The movie is live action, so we can assume Mr. Ohno worked on the storyboards and animatics. It was released in Japan, Hong Kong, and Taiwan.

Ikko Ohno in February 2019, still working as a graphic artist. (Image courtesy of Ikko Ohno @ Sangikyo)