Abstract

This article is a contextual historical study focused on the restoration process of a Finnish educational PC game, Promille (Tietotoimisto, 1990). In 2017, a floppy disk containing the previously unknown (to historians and hobbyists) game was found by chance in the city woods of Tampere, Finland. These unusual circumstances and the following repair efforts, undertaken as a collaboration between the local retrogaming circles and the Finnish Museum of Games in Tampere, attracted national media attention. This paper aims at reconstructing and contextualizing these events while at the same time reflecting on the cultural practices of maintenance and repair at public and private memory institutions in Finland, and how the case of Promille has affected the local heritage community. The study contributes to the theoretical discussions around the heritagization of games and revisits Alois Riegl’s concept of unintentional monuments in relation to game cultures.

Introduction

In the context of game preservation most writers have discussed the survival of digital games and gaming devices with the shared understanding that we should look beyond solutions that entail running data in its original form and on original devices.4 Data migration and emulation should be considered as alternative and viable means for preserving games, since the whole idea of preserving “original gaming experiences” can be disputed.5 Defining the meaning of original has also proven difficult or even impossible since games exist in countless versions across various platforms. Additionally, gaming as cultural practice is embodied by real players and situated in actual places and practices.6 A shift of focus, from playable artifacts to the documentation of play, would enable us to better address these issues.7

However, previous discussions have not quite touched on issues related to maintenance and repair. As Andrew Russell and Lee Vinsel remind us, maintenance is an essential, much more general practice of continuation and conservation than repair, and we can learn a lot from closely examining the identity of maintainers themselves.8 The historiography of technology has largely overlooked maintenance and instead focused on inventions, innovations, and novelties rather than on the persons and practices that keep, for example, sewer and electricity systems or web services running year after year.

We must also remember the complexity of maintenance and repair. Everyday maintenance of things and processes can become preservation when the danger of a technological breakdown exists but a common understanding of the technology’s cultural value, and thus the need to conserve it, remains. The need for preservation can also take place after rediscovery of something lost and not maintained. When talking about preservation of old digital games, on one hand, we can approach the issue as a technical and practical hands-on question of maintaining old hardware and software. On the other hand, questions of game preservation, repair, and maintenance relate to our cultural values, needs, and imagination. We can approach these issues in the context of heritage processes, where questions regarding institutional self-reflection, cultural inclusion, and institutional gatekeeping, as well as a need for added reflexiveness, gain center stage.9

This article aims at reconstructing and contextualizing the history behind the discovery and restoration of Promille, a previously unknown Finnish educational PC game published in 1990 by Alko, the national alcoholic beverage retailing monopoly of Finland. In 2017, the game was accidentally found in a city park, and the subsequent media and public interest was unprecedented in Finnish game-heritage circles. This case study explores not only technical but also cultural layers of game preservation, repair, and maintenance plus the various ways that related material practices are embedded in the local cultural context. Who are the main stakeholders in these processes and how do they interact and collaborate? Furthermore, this paper contributes to the theoretical discussions of heritagization and revisits monumentalization in relation to game cultures.10

The following findings result from a contextual historical study that involved critically examining various historical sources and closely analyzing the game itself. We have applied methods that Finnish historians Mirkka Danielsbacka, Matti O. Hannikainen, and Tuomas Tepora call basic methods of historical study: source criticism, contextualization of the research object, and hermeneutic or theoretical thinking that takes place during the writing process.11 We have conducted a complete survey of Alko’s staff and customer magazines (1985–95) as well as the company’s yearly reports and other available materials related to corporate history from the period.12 We also unsystematially reviewed social-media posts and newspaper articles focused on the discovery of Promille. Furthermore, we interviewed archivists and museum curators who participated in the repair process, and we corresponded with the legacy businesses involved in developing and publishing the game.

From a historiographical perspective, telling the story chronologically has proven less meaningful than starting from the discovery and proceeding to the game’s origin and cultural restoration as a heritage object. Hence, we first reconstruct the sequence of events that began with a Facebook post documenting the initial discovery of the game. We closely follow the artefact’s identification and subsequent repair efforts, as well as the related media attention, up to Promille’s full restoration and exhibition at the Finnish Museum of Games (FMG). Second, we focus on the actual gameplay and historical contextualization of the game’s development. Third, we proceed to the methodological and theoretical framing of the Promille case. We position the game as a historical object and as an unintentional monument.13 We then reflect on the cultural practices of maintenance and repair at the public and private memory institutions (i.e., libraries, archives, and museums) in Finland, and how the case has affected the local heritage community.

Chronological Reconstruction of the Events

A Discovery in the Woods of Tampere

Who would expect a piece of forgotten game history to be found in the woods? Yet the story behind the restoration and monumentalization of Promille starts in the forest area of Kauppi Park in the postindustrial city of Tampere, Finland. The creation of this large public recreational space near the city center, what Nordic countries call a folkpark, followed a labor-movement initiative in the late nineteenth century to benefit working-class citizens.14 To this day, it remains a popular place for outdoor activities, such as walking, jogging, orienteering, and game playing.

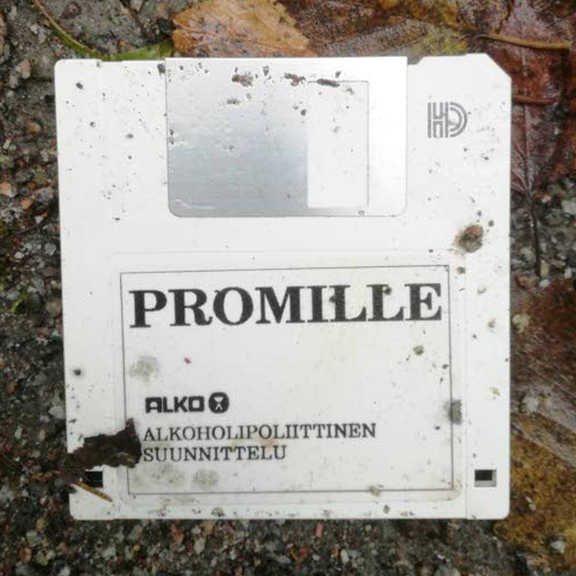

On September 9, 2017, a professional archivist and retrogaming hobbyist in his late thirties, Pekka Kauranen, was jogging in Kauppi Park when he accidentally came across a peculiar scene. Off the beaten track in the middle of the forest, surrounded by fir trees, there was a secluded place that looked like a makeshift encampment. In the moss, among other items such as plastic bags and clothing items, he found a 3.5-inch floppy disk. It was covered in mud, but one could read the label “Promille” and recognize the logo of Alko. Not wanting to intrude in case somebody (e.g., a homeless person) was living there, he decided to take some pictures of the disk and post them on Facebook but otherwise left the objects untouched (see fig. 1). When he finally got home and thought about his discovery more, Kauranen realized that his first impression was probably wrong and that the site was likely abandoned. He decided to go back.15

Figure 1

In the meantime, Kauranen’s friend with a similar background and shared interest in retrogames, Martin Zechner, saw the post on social media. He immediately had a feeling that the disk might be something important and should not just be left in the forest. As it was raining, Zechner decided to visit the site the next day. Even though he got detailed coordinates, he was not able to find Promille at first. Undeterred, he kept looking, and on the following day, he was finally able to locate and retrieve the disk. When Kauranen came back to the location of his original discovery, he was no longer able to find Promille, as Zechner had beaten him to it. Yet after further inspecting the surroundings, Kauranen picked up what could have been the cover of the disk.

Initially, the two friends were not sure what to do about their findings. They contemplated trying to get the disk running on an old PC but were not able to proceed due to the disk’s very bad condition. However, a closer examination of the discovered objects revealed more clues. The cover said it was a game called Hup-Peli (Arts and Minds, 1987); Kauranen recognized the name of a game as one on display at the FMG, which had opened in Tampere earlier that year.16 However, the other side of the cover mentioned an unknown educational game called Pulssi.

Ten days later, on September 27, Kauranen and Zechner decided to contact the FMG. The institution was excited about the discovery, and curator Outi Penninkangas agreed to meet Kauranen on October 2. They were joined by Mikko Heinonen from the Pelikonepeijoonit retrogaming group, a long-standing supporter of the museum. At the meeting, Kauranen, Penninkangas, and Heinonen hypothesized that the recovered media might somehow be related to Alko’s game Hup-Peli. On the disk cover, they noticed some very faint marker-pen lettering, barely visible after the disk’s long exposure to the elements. The lettering seemed to spell out the name “Promille,” but as there was no existing information on a game called Promille, they were still not able to solve the mystery. Regardless, Penninkangas decided to start a video project about the forest discovery, and the museum staff interviewed Kauranen virtually.

Digitalization Process Conducted in a Bunker

In order to inspect the disk’s contents, FMG contacted the hobbyist group Kasettilamerit, known for their expertise in digitizing old magnetic media.17 While Kasettilamerit started out with an interest in Commodore computers, the collective had expanded its scope to other platforms and media and also provided digitalization services to the National Library of Finland. By chance, the group was organizing one of its digitalization meetups in Tampere from October 27 to 29, 2017. It was decided that researcher Niklas Nylund (FMG), together with the original search party (Kauranen and Zechner), would go to the event, which would take place in the Kasettilamerit underground premises, a former air-raid shelter in the Tampere district of Epilä.

Figure 2

Promille disk during the restoration process (Courtesy of Kasettilamerit)

Tommi Lempinen handled the restoration process of Promille, a task that proved difficult. As Lempinen recalls, “there were extra challenges despite the magnetic media itself being fairly clean.”18 When the floppy disk arrived at the bunker, the mud and any remaining soil particles had been mostly removed by the FMG conservators. Yet the internal mylar platter (actual data-storage media) had detached from the round stainless-steel hub in the middle of the casing that engages with the disk drive motor (see fig. 2). Thinking back on the events five years later, Lempinen believes that exposure to the elements likely caused deterioration of the glue used on the adhesive ring to secure the media to the hub. As a remedy, he used double-sided tape to attach the unprotected platter to the hub and move them both into another clean disk case.

Next, he attempted to create a raw image of Promille using his KryoFlux device. The repair process attracted many spectators, excited for the mystery to finally be solved. Unfortunately, manually reattaching the platter to the hub affected the procedure and what normally would have taken five minutes lasted several hours. Lempinen explains: “the positioning of the platter relative to the hub is important on a used disk. To make manufacturing easier, there is some room left for the platter to move on the hub, and when a disk is formatted for use, the disk drive lays out the circular tracks where the read/write heads are positioned inside the drive. Each manufactured disk drive is thus calibrated at a factory, such that they read exactly in the same position.”19 This design allows the floppy disk to be erased, rewritten, and read again, interchangeably, by any 3.5-inch drive. However, at this point, the position of the Promille platter was not aligned with the standard calibration of the disk drive. Even worse, as the platter was rotating, it was drifting into random positions. Lempinen recalls that “it took many attempts to image the disk, removing and reattaching the platter to the hub with small changes to its position, while also making sure the platter [was] kept clean from fingerprints and dirt.”20 This was in fact a very precise process, as the margin of error was only 0.2 mm. After many hours of strenuous work, Lempinen was gradually able to read the disk sector by sector. Thankfully, he had dealt with a detached platter earlier that year. His customized disk drive and self-made assist program contributed to the success. Reflecting on the entire procedure, the hobbyist conservator points out that “unless someone comes up with an idea for how to magnetically analyse the platter and place it on the centre hub, and at the exactly correct position, the same process would still have to be performed [today].”21

After Lempinen restored the whole disk, those present in the bunker could see for themselves what the media contained. Rather than another copy of Hup-Peli, it held an educational game called Promille: a game previously entirely unknown to historians and retrogaming hobbyist circles.

The Story of the Legendary Game Goes Viral

Soon after the disk was digitized, Marjo Rämö, a journalist working for the local newspaper Tamperelainen, got interested in Promille, having heard about it from Penninkangas while working on another story. Soon after, on November 9, 2017, the paper printed Rämö’s article on the discovery, and the account went viral across Finland. Other media outlets contacted the FMG in order to report on the story. For example, the largest newspaper in the country, Helsingin Sanomat, published its own article, as did the tabloid Ilta-Sanomat, computer hobbyist magazine MikroBitti, and many more.22 Most articles focused on the peculiarity and bizarreness of the initial discovery in the city woods. Juuso Määttänen wrote “if one were to start listing places to begin looking for Finnish digital history, Kauppi forest in Tampere would not be near the top of the list.”23 In addition to introducing the discovery, Määttänen presented an overview of the game and digitalization process based on interviews with Lempinen and Nylund, and he ended the article by asking when the game would be playable at the FMG. Nylund promised to make the game playable as soon as possible, with a target date set to coincide with the museum’s first anniversary celebration in January 2018.

Yet the media interest was relatively short-lived, peaking in November 2017. When the restored Promille was shown at the anniversary party, only the Finnish national television YLE took notice of the occasion. The Kasettilamerit group gained added attention in the media when their experts talked about the importance of game preservation, and visitors were able to play educational games on original hardware. Still, the game did not seem to live up to the mystery presented in the press.

The unusual context of the disk’s discovery probably accounts for the story’s wide circulation. Because no one knew anything about the game’s existence or its creator before it was found, the mystery intensified. The media could not ignore such a good story, and the recent opening of a national game museum made the whole situation more topical. The awareness of game heritage also motivated the local paper Tamperelainen to report on the story. However, when the game itself proved to be a relatively simple educational product about the dangers of alcohol consumption, media interest faded fast.

Impact on the Heritage Community

Benefiting from the media attention, FMG staff reached out to possible informants about the origins of Promille. Soon they established that Arts & Minds Oy, formerly Tietotoimisto Erkki Haaramo, produced the game—the same company that made Hup-Peli. The business was still in operation but it had not preserved any information on the game. The owners, however, were interested in hearing more about the game and asked the FMG to share a copy. An image file of Promille was sent and the company promised to go through their archives once more, hoping to find some new evidence. Alko had likewise renewed its interest in the game and contacted the FMG regarding potentially publishing a port of Promille online. However, after the initial wave of enthusiasm from everyone involved, this idea did not materialize.

Figure 3

Promille among other received examples of educational software of the era (Courtesy of the Finnish Museum of Games’ Facebook profile)

Other individuals and institutions intrigued by the news story contacted FMG. It turned out that two other Finnish organizations had a copy of the game in their collections as well as other early Finnish educational games that were then unknown to hobbyists and researchers (see fig. 3). The UKK Institute had a small collection of pamphlets and other types of educational materials related to various intoxicants and public health.24 In fact, at the time, the institute was in the process of dissolving its ephemera archives because the long-time archivist who had lobbied to protect the material was soon to retire. The UKK therefore decided to donate its educational game collection (roughly ten titles) to the FMG because the games were simply too unconventional for the institute to preserve.

The FMG was also contacted by the Lohtaja secondary school from Kokkola which had decided to donate its copy of Promille, too. Most likely, the school had obtained the game during its original release, and it might have been used in classes. Additionally, the school had a copy of Hup-peli displayed in the school corridor display case, and the schoolteacher who contacted the FMG was very excited that these were in fact the games discussed on social media. These small archives and their (part-time) workers had been completely unaware of the growing historical interest in Finnish games. Clearly, despite all the media attention and the budding interest in game history, the great potential of the games these unsung heroes had preserved for decades still remained untapped.

Although the media attention dwindled, it contributed to an ongoing public discussion on the preservation of games. It also introduced new collaborations with small local archives and made their collections suddenly topical—at least for a brief time. Collaboration also heightened awareness about the heretofore largely unknown history of Finnish educational games and their precarious position in archives and institutions.25 This institutional interest in educational games also affected the local retrogaming and hobbyist scenes and shifted their interest from traditional commercial games to the fringes of game publishing, such as the surprisingly engaging history of Finnish educational games.

Close Reading and Historical Contextualization

Gameplay

As discussed above, the media attention around Promille quickly faded because the game itself is a very simple point-and-click affair, limited even for the standards of the time. In fact, it can be disputed whether it is a game at all, or just a gamified remediation of an alcohol test employing experiential learning techniques. As a game, it consists of two different views, one of a virtual bar and another of an alcohol fact sheet (see fig. 4). The latter has sixteen educational and informative themes, ranging from general health effects to the physiology of a hangover and youth alcohol usage. At the bar, which is visually very simple, the player is able to order a schnaps, a glass of beer, a small bottle of wine, or “a delicious dish.” The miniature cargo ship on the top shelf, above the beverages and cutlery, might refer to the passenger ferries between Finland and Sweden commonly used for heavy partying and drinking, as well as for gaming.26

Figure 4

Screenshot of Promille ’s main menu (Courtesy of the Finnish Museum of Games)

Like most of the software produced in Finland, Promille has two language options: Finnish and Swedish (official languages), and as a bonus also English. Its installation instructions, dated January 21, 1990, present minimum requirements for a PC computer: MS-DOS operating system, 640 KB central memory, hard disk with 3 MB space, VGA graphics card, monitor, and a mouse, which are standard specifications for a machine of that era. In the game, the player can define their sex, height, and weight, which are standard categories used in measuring the level of intoxication. The game also presented how many hours it would take for alcohol to be removed from the bloodstream. In that sense, Promille serves as nothing more than a visually enhanced version of a classic alcometer utility program. However, it also offers playful, if not transgressive, engagement. After playtesting the game, we can speculate that the teenage players in the 1990s would enjoy exploring various strategies to get the bar alcometer to the maximum level.

As such, Promille is a much more limited game than the educational PC adventure game Hup-peli produced by the same company. The obvious differences in scope between the two games become even more distinct when we take into account that Hup-peli was published three years earlier and only had CGA graphics. Therefore, it seems possible that Promille was merely a playable demo, not a fully realized commercial product. That all known copies of Promille were delivered inside cover sheets of other educational software supports this supposition. But why was the game made in the first place?

Publisher Background and Finnish Educational Software in the Late 1980s

The publisher of Promille, Alko, was established at the end of the Finnish prohibition period (1919–32).27 Alko’s role in Finnish society can be considered as rather ambivalent, or even controversial. On one hand, it makes money on alcohol sales, and on the other, it allegedly prevents overconsumption.28 As a result of its social responsibility, Alko ran public campaigns on alcohol abuse. Since 1951, and even more actively from the 1970s onward, Alko published educational posters and other printed or audiovisual materials aimed at preventing alcoholism and supporting other means of public alcohol policy.

Alko was also open to the use of new media in its campaigns.29 The PC games Hup-peli (1987) and Promille (1990) were connected to these campaigns and were targeted mainly at secondary school pupils. It seems that there was also a related educational program, Pulssi (1988?), developed for the Commodore 64 computer. Thus far, the data file is missing, but based on a cover sheet in which Promille was originally discovered, we know it offered an overview of Finnish statistics related to short- and long-term alcohol use. A commonality among all these games is that very little information can be found about them.

Unfortunately, there is no existing historical research on the Finnish educational games of that era. It seems that at the end of the 1980s, the educational software market in Finland was very small. Only a couple of Finnish companies developed educational games for the local market, and few localized versions of internationally developed educational software were available, despite a growing demand for such products because of the ongoing computerization of schools.30 As mentioned above, both Hup-peli and Promille were developed by a small studio called Tietotoimisto, led by Erkki Haaramo and based in the Helsinki area.31 The company focused mostly on developing utility software but produced some educational games on the side and not only for Alko. For example, Tietotoimisto produced the game Tupakistan 2200 (1987–88), which dealt with the disadvantages of smoking, for the National Board of Health (Lääkintöhallitus) and the Youth Education Association (Nuorisokasvatusliitto ry).

To date, we have not been able to establish if Tietotoimisto developed these games on its own or as a result of a commission. The second option seems more likely, as usually, these were contracted custom-made products, responding to the very specific needs of the state. Furthermore, competing with internationally made educational software was difficult, if not overall unrealistic, due to the limited resources. Similarly, it was not possible to challenge any of the commercial games, as such titles had much bigger budgets and a higher production value. In general, Finnish educational game development was a niche, one that was neither socially impactful nor financially viable. The few games that were produced had limited circulated. They also cost about ten times more than games made for the mass commercial market, since they were sold for use in school classrooms.

Theoretical and Methodological Contextualization

From Finnish Forest to New Mexican Desert, or Vice Versa

In this article we argue that the discovery of Promille in the woods also led to its discovery as an important carrier of historical meaning.32 The story of Promille echoes in many ways the rediscovery of E.T. the Extraterrestrial (Atari, 1982). Excavated in the New Mexico desert, the once-abandoned cartridges are now exhibited in game history museums across the world.33 As Guins observes, “video games [in general] were never intended for deliberate commemoration and ... [as such are] attuned with Alois Riegl’s description of unintentional monuments.”34 Riegl’s insightful reflections on monuments and the different aspects of their cultural value will serve as a theoretical point of departure for our close analysis of how Promille became a heritage object.

To answer the question of how Promille became an unintentional game monument, we had to know what the game’s intended role and character had been when it was originally introduced in 1990. Unfortunately, not much primary source material is available, which probably points to the limited significance of Promille at the time of its release. On the other hand, when we contextualize the game, we see that it represents an early Finnish digital educational game and demonstrates Alko’s interest in using new media in its campaigns. Thus, the game opens new avenues for the cultural history–oriented study of games.

Upon its release, Promille’s impact might have been small or minor.35 Interest in the game has peaked only recently because of the sensational rediscovery that took place only a couple of months after the opening of the FMG. However, the game is also interesting from a media archaeological point of view. Jussi Parikka defines media archaeology as: “a way to investigate the new media cultures through insights from past new media, often with an emphasis on the forgotten, the quirky, the non-obvious apparatuses, practices and inventions. In addition, ... it is also a way to analyse the regimes of memory and creative practices in media cultures—both theoretical and artistic. Media archaeology sees media cultures as sedimented and layered, a fold of time and materiality where the past might be suddenly discovered anew, and the new technologies grow obsolete increasingly fast.”36 According to this definition, Promille is clearly a media archaeological object, or as Andrew Reinhard would put it, an object of archaeogaming.37 While it was not excavated from the ground, it was literally discovered on the ground. Furthermore, the process of restoration and repair of the disk was a case of data excavation, where the data was laboriously reconstructed from countless fragments. In the media archaeological sense, the Promille disk, with its somewhat misleading cover, is a forgotten and ambiguous game-historical object. Its story consists of many layers of historical sediment, from institutionalized alcohol education, school teaching, and budding game cultures to the early days of the Finnish software industry.

We can also investigate the situation from the contemporary legal perspective: the Finnish Heritage Agency defines antiquities as “movable ancient objects that are at least 100 years old and that do not have a known owner.”38 In that case, according to Finnish law, Promille is not an ancient monument protected by the Antiquities Act 295/1963 but simply lost property to which the Lost Articles Act 778/1988 applies. In theory, the disk should have been returned to the regional lost-and-found services. However, we can speculate that if it was uncovered by someone else—for example, a person dedicated to environmental preservation—they would consider the abandoned location as illegal littering and describe the items lying around in the Kauppi forest as mixed waste. Yet as this is an area maintained by the city of Tampere services, it is more likely that any local passerby would leave that task to the responsible authorities. And this, in fact, is what the two retrogaming enthusiasts did.

Unintentionality and Riegl's Theory of Monuments

The writings of the Austrian art historian Alois Riegl (1858–1905) greatly influenced Western humanities, and they directly inspired, for example, Walter Benjamin’s work on aura, as well as many other researchers and practitioners in the areas of art history, conservation, and media.39 In the 1980s and 1990s, Riegl’s theory of monuments was particularly prevalent in European memory studies discussing state memorials dedicated to Holocaust and communist-state victims, which were being erected across the continent.40

Riegl begins his 1903 article The Modern Cult of the Monument: Its Character and Its Origin, with a simple observation: the meaning of the concept of monument has changed over time. In its original sense it described “a work of man erected for the specific purpose of keeping particular human deeds or destinies … alive and present in the consciousness of future generations.”41 However, he quickly recognized that such “deliberate monuments” (emphasis in original) differed from what his contemporaries had in mind when they discussed preservation of monuments. To the contrary, they were interested in works of art or broadly understood remnants of the past that were usually created without considering future commemoration: “[i]n case of deliberate monuments, the commemorative value is dictated to us by others (the former creators), while we define the value of unintentional monuments ourselves.”42 The distinction between intentional and unintentional monuments is only one of many theoretical contributions this paper brings to heritage studies, yet perhaps the most relevant.

However, as Lisa Regazzoni points out, intentionality was an important category even before Riegl, not only in European historiography but also specifically in the Western discourse surrounding monuments.43 For example, in 1857 in a series of influential lectures at the University of Berlin, Prussian historian Gustav Droysen “used the intentionality criterion to distinguish the different types of historical materials … that historians deal with in their research,” which include: remains, sources, and monuments.44 In Droysen’s typology, Promille could be initially considered as remains, something that was “neither deliberate … nor had … been handed down intentionally to serve future memory.”45 Yet as the game made its way into the FMG, it became a cultural and historical monument. According to Regazzoni, the latter for Droysen usually had a hybrid nature. While it was a relic of the past, it could still be a useful source for historical research.

This brings us back to Riegl’s article, in which he further discusses three different types of commemorative values a monument can represent: age value, historical value, and deliberate commemorative value. According to the principles of age value, “the aesthetic effect of a monument … arises from signs of decay and the disintegration of the work’s completeness through the mechanical and chemical forces of nature.”46 Somewhat in contrast, “a monument’s historical value increases the more it remains uncorrupted and reveals the original state of creation.”47 Yet, in true opposition of the age value is the deliberate commemorative value, as “the fundamental requirement of deliberate monuments is restoration.”48 Next, Riegl considers monuments from their present-value perspective and practical demands of contemporary use. As Lucia Allais and Andrei Pop (2020) aptly summarize, what can be called Rigel’s method “consists in abstracting from historical objects their varying capacity to satisfy a catalogue of modern values, often contradictory but all equally legitimate for the public interest and then asking for a compromise to achieve the greatest possible consensus” (emphasis in original).49 This approach is visible in his work as a monument commissioner for the Habsburg government in which he advocated for preservation of the various layers of history uncovered during the restoration of wall paintings at the Wawel Cathedral in Kraków.50

Although it involved media attention, the restoration of Promille did not require any public consensus. Its historical value could have been easily reestablished, as it became a playable object again without any loss to its original potential. None of the heritage stakeholders involved wanted to abandon the artefact in the woods where it would become another sad monument of the Anthropocene rather than ludic history. It seems that what was unique about the monumentalization of Promille was predominantly its inherent unintentionality as a cultural heritage object and the commemorative value attributed to it by the media. After all, “a monument is an active element in a dynamic network of cultural heritage processes.”51

Conclusion

As discussed in previous sections, maintenance can refer to the everyday work that assures the functionality of everyday infrastructures such as archives and museum collections, but it can also refer to heritage work performed by volunteer hobbyists and museum experts to keep obsolete technologies, such as steam locomotives or computers, from becoming obsolete. From this perspective, maintenance and repair are related to the ongoing discussions among cultural heritage preservationists.

First, following Shannon Mattern as well as Andrew Russell and Lee Vinsel, it is important to shed light on the low-paid and financially vulnerable fringes of the archival sector.52 In Finland, very small archives that are scattered around the country do large amounts of heritage work. The collections of municipalities and parishes are endangered, as are those of schools, rural universities, and other peripheral educational institutions that are not directly tied to the larger national discussion on preservation. Unique minor collections, such as the UKK or Lohtaja school collections of educational games, can theoretically be found anywhere in the country, but they can just as easily disappear. These small archives are often formed ad hoc and based on the interests of an individual archivist. Budget concerns make these institutions especially vulnerable in the current fiscal climate. The media attention to Promille brought to light an existing lack of communication among game collectors, amateur historians, and these small archives. Promille existed in these collections, but only a few people knew about it.

Second, the case of Promille shows the limits of a hobbyist historian–led game-preservation discourse, which can easily exclude marginalized games and genres. The Tampere woods discovery and its subsequent resolution made hobbyists realize how, while documenting the history of Finnish games, they had entirely ignored the educational sector. At the same time, the mystery of Promille played a key role in shifting the focus of the national game-heritage discussion in Finland from a collector mindset to a more nuanced cultural-heritage mindset, especially since the FMG provided a place to preserve these artifacts and then use them for exhibitions and pedagogical programs.53 The technical repair of the game occurred parallel to the cultural restoration, which spurred a heightened sense of the importance of educational software as game heritage. We need institutions like the FMG to reinterpret the meaning of these marginalized games and understand them as part of the Finnish, and perhaps even global, game heritage. As Mattern points out, it is a policy choice for collections to preserve marginalized games that popular media has overlooked.54

Third, the case made quite apparent the dependence of the entire Finnish heritage domain on hobbyist preservationists for the repair and maintenance of old digital media. The other unsung heroes of Kasettilamerit, those that have been digitizing our shared digital heritage when larger heritage organizations lacked the skills and motivation to delve into the world of old media and digitization, brought closure to the Promille story by making the game playable once more. Still, when the game did not live up to the media hype, everything was soon forgotten again. The media craves sensationalism, not the mundane work of archivists and hobbyists. We must assure that this kind of maintenance and safekeeping of marginalized topics happens even without viral news stories on social media, and that institutions and preservationists must persevere even without public demand for it.

In the end, repair revealed an unexpected monument. The story intrigued journalists because of the mystery of an unknown artefact being found in the woods. The restoration process resembled solving a jigsaw puzzle, but one where the process was more interesting than the completed picture. The incident brought to the fore the blind spots in national game preservation efforts and unearthed the excluded members of the heritage community. The story of Promille may teach us that marginalized game heritage is and has been preserved by the unrecognized heritage actors working in archives and hobbyist groups. But this knowledge is not and has never been that interesting in the eyes of the media.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Academy of Finland project Centre of Excellence in Game Culture Studies (CoE-GameCult, [353268]).

Footnotes

1. ^ Wendy Hui Kyong Chun, “The Enduring Ephemeral, or the Future Is a Memory,” Critical Inquiry 35, no. 1 (Autumn 2008): 171, https://doi.org/10.1086/595632

2. ^ Lisa Regazzoni, “Unintentional Monuments, or the Materializing of an Open Past,” History and Theory 6, no. 2 (June 2022): 268, https://doi.org/10.1111/hith.12259

3. ^ Andrew L. Russell and Lee Vinsel, “After Innovation, Turn to Maintenance,” Technology and Culture 59, no. 1 (January 2018): 13, https://doi.org/10.1353/tech.2018.0004

4. ^ For example, see Mark Gutenbrunner, Christoph Becker, and Andreas Rauber, “Keeping the Game Alive: Evaluating Strategies for the Preservation of Console Video Games,” International Journal of Digital Curation 5, no. 1 (June 2010), http://www.ijdc.net/article/view/147/209; Henry Lowood et al., “Before It’s Too Late: Preserving Games across the Industry/Academia Divide,” in Proceedings of DiGRA2009: Breaking New Ground; Innovation in Games, Play, Practice and Theory (London: Brunel University, 2009), http://www.digra.org/wp-content/uploads/digital-library/09287.29025.pdf .

5. ^ See Melanie Swalwell, “Moving On from the Original Experience: Philosophies of Preservation and Dis/Play in Game History,” in Fans and Videogames: Histories, Fandom, Archives, ed. Melanie Swalwell, Angela Ndalianis, and Helen Stuckey (London: Routledge, 2017), 213–33.

6. ^ For example, see Allison Gazzard, “Between Pixels and Play: The Role of the Photograph in Videogame Nostalgias,” Photography and Culture 9, no. 2 (2016): 151–62, https://doi.org/10.1080/17514517.2016.1203589; and Olli Sotamaa, “Artifact,” in The Routledge Companion of Video Game Studies, ed. Mark J. P. Wolf and Bernard Perron (New York: Routledge, 2014), 3–9.

7. ^ For example, see Olle Sköld, “Understanding the ‘Expanded Notion’ of Videogames as Archival Objects: A Review of Priorities, Methods, and Conceptions,” Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology 69, no. 1 (January 2018): 134–45, https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.23875; and Niklas Nylund, “Game Heritage: Digital Games in Museum Collections and Exhibitions” (PhD diss., Tampere University, 2020), https://trepo.tuni.fi/handle/10024/123211.

8. ^ See Russell and Vinsel, “After Innovation,” 1–25.

9. ^ See Laurajane Smith, Uses of Heritage (London: Routledge, 2006); Jaakko Suominen and Anna Sivula, “Participatory Historians in Digital Cultural Heritage Process: Monumentalization of the First Finnish Commercial Computer Game,” Refractory: Australian Journal of Entertainment Media 27, no. 1 (2016), https://web.archive.org/web/20160903020905/http://refractory.unimelb.edu.au/2016/09/02/suominen-sivula; and Jaakko Suominen, Anna Sivula, and Maria B. Garda, “Incorporating Curator, Collector and Player Credibilities: Crowdfunding Campaign for FMG and the Creation of Game Heritage Community,” in “Preserving Play,” ed. Alison Gazzard and Carl Therrien, special issue, Kinephanos: Canadian Journal of Media Studies, August 2018, https://www.kinephanos.ca/2018/incorporating-curator-collector-and-player-credibilities-crowdfunding-campaign-for-the-finnish-museum-of-games-and-the-creation-of-game-heritage-community.

10. ^ Laurajane Smith, Emotional Heritage (London: Routledge, 2020).

11. ^ Tuomas Tepora, Mirkka Danielsbacka, and Matti O. Hannikainen, “Johdanto: Tutkimuksen työkalut,” in Avaimia menneisyyteen: Opas historiantutkimuksen menetelmiin, ed. Tuomas Tepora, Mirkka Danielsbacka, and Matti O. Hannikainen (Helsinki: Gaudeamus, 2022), 14–17.

12. ^ Since 1965, Alko has published a quarterly customer magazine initially called Viiniposti and more recently Etiketti. In the period from 1945 to 1998, the company also issued a bimonthly employee magazine entitled Pulloposti.

13. ^ Regazzoni, “Unintentional Monuments,” 259; and Alois Riegl, “The Modern Cult of Monuments: Its Essence and Its Development,“ in Historical and Philosophical Issues in the Conservation of Cultural Heritage, ed. Nicholas Stanley Price, M. Kirby Talley Jr., and Alessandra Melucco Vaccaro, trans. Karin Bruckner with Karen Williams (Los Angeles: Getty Conservation Institute, 1996), 69–83, originally published as Der moderne Denkmalkultus: Sein Wesen und seine Entstehung (Vienna: W. Braumüller, 1903).

14. ^ Maunu Häyrynen, Maisemapuistosta reformipuistoon: Helsingin kaupunkipuistot ja puistopolitiikka 1880-luvulta 1930-luvulle (Helsingfors: Helsinki-Seura, 1994).

15. ^ Pekka Kauranen, email to Niklas Nylund, 2022.

16. ^ A wordplay combining two partially homophonic Finnish words: huppeli (meaning slightly intoxicated) and peli (a game) to create a funny-sounding pun.

17. ^ The group was officially established in 2011 as an association dedicated to archiving data related to magnetic and optical media. Over the years the group has archived data from tapes and floppy disks of many various platforms and helped, for example, the Software Preservation team to archive thousands of original titles. The Kasettilamerit also organizes events dedicated to data archiving at least few times a year. See Kasettilamerit, “About,” https://kasettilamerit.fi/en/about/.

18. ^ Tommi Lempinen, email to Niklas Nylund, 2022.

19. ^ Lempinen, email.

20. ^ Lempinen.

21. ^ Lempinem.

22. ^ “Tamperelaisesta metsästä löytyi vuosikymmeniä vanha disketti, josta ekspertit onnistuivat kaivamaan sisällön:Löytyi 1980-luvulla tehty Alkon valistuspeli, jossa voi juoda itsensä hengiltä,” Helsingin Sanomat, November 14, 2017, https://www.hs.fi/nyt/art-2000005448426.html.

23. ^ “Tamperelaisesta metsästä,” translation by author.

24. ^ UKK Institute (Centre for Health Promotion Research) is a private research organization based in Tampere that focuses on public health. It was founded in 1980 and named after the former president of Finland, as well as enthusiastic sportsman, Urho Kaleva Kekkonen (UKK, 1900–1986).

25. ^ For more on the preservation of educational games, see Maria B. Garda and Jaakko Suominen, “In Memory of Memory Gliders: Preservation of EU-Funded Serious Games as Digital Heritage,” in Engaging with Historical Traumas, ed. Nena Močnik et al. (London: Routledge, 2021), 257–70.

26. ^ Jaako Suominen and Anna Sivula, “A Place for a Nintendo? Discourse on Locale and Players’ Topobiographical Identity in the Late 1980s and the Early 1990s,” in Game History and the Local, ed. Melanie Swalwell (Cham, Switzerland: Springer, 2021), 91.

27. ^ Interestingly, the exact time when the Alko stores first opened, April 5, 1932, at 10:00 a.m., is a very well-known date in Finland as it is a popular pub quiz question.

28. ^ See Martti Häikiö, Alkon historia: Valtion alkoholiliike kieltolain kumoamisesta Euroopan unionin kilpailupolitiikkaan 1932–2006 (Helsinki: Otava, 2007); and Matti Virtanen, “Alkon kaksinaisuus,” Alkoholipolitiikka 56, no. 3 (1991): 163–64.

29. ^ Häikiö, Alkon historia, 311; and Mirja Vepsäläinen, “Haittavalistus esittäytyi avoimien ovien päivänä,” Pulloposti 4 (1988): 16.

30. ^ Petri Saarikoski, “Bittinikkareista tulevaisuuden päätöksentekijöitä? Tietokonelukutaito ja koulujen atk-opetuksen alku Suomessa 1980-luvulla,” in Välimuistiin kirjoitetut: Lukuja Suomen tietoteknistymisen kulttuurihistoriaan, ed. Petri Saarikoski et al. (Turku: k&h, 2006), 80–108.

31. ^ The literal translation of Tietotoimisto from Finnish: Knowledge Office or News Agency.

32. ^ Regazzoni, “Unintentional Monuments,” 259.

33. ^ See Raiford Guins, Game After: A Cultural Study of Video Game Afterlife (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2014), 207–35; and Andrew Reinhard, Archaeogaming: An Introduction to Archaeology in and of Video Games (New York: Berghahn, 2018), 23–29.

34. ^ Guins, Game After, 108.

35. ^ On the concept of minor platforms, see Benjamin Nicoll, Minor Platforms in Videogame History (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2019).

36. ^ Jussi Parikka, What Is Media Archaeology? (Cambridge, UK: Polity Press, 2012), 2–3; see also Erkki Huhtamo and Jussi Parikka, “Introduction: An Archaeology of Media Archaeology,” in Media Archaeology: Approaches, Applications, and Implications, ed. Erkki Huhtamo and Jussi Parikka (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2011), 1–21.

37. ^ See Reinhard, Archaeogaming.

38. ^ Päivi Maaranen, “Antiquities, Ancient Monuments and Metal Detectors: An Enthusiast’s Guide,” in The Finnish Heritage Agency’s Guidelines and Instructions 13 (Helsinki: Finnish Heritage Agency, 2020), 20, https://www.museovirasto.fi/uploads/Palvelut_ja_ohjeet/Antiquities_and_metal_detectors_guide_2020_final.pdf.

39. ^ See Lucia Allais and Andrei Pop, “Mood for Modernists: An Introduction to Three Riegl Translations,” Grey Room, no. 80 (Summer 2020): 6–25, https://doi.org/10.1162/grey_e_00300.

40. ^ See Mechtild Widrich, “The Willed and the Unwilled Monument: Judenplatz Vienna and Riegl’s Denkmalpflege,” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 72, no. 3 (2013): 382–98, https://doi.org/10.1525/jsah.2013.72.3.382.

41. ^ Riegl, “The Modern Cult,” 69.

42. ^ Riegl, 72.

43. ^ Regazzoni, “Unintentional Monuments.”

44. ^ Regazzoni, 246.

45. ^ Regazzoni.

46. ^ Riegl, “The Modern Cult,” 73.

47. ^ Riegl, 75.

48. ^ Riegl, 78.

49. ^ Allais and Pop, “Mood for Modernists,” 9.

50. ^ Alois Riegl, “On the Question of the Restoration of Wall Paintings,” trans. Ittai Weinryb and Max Koss, West 86th: A Journal of Decorative Arts, Design History, and Material Culture 27, no. 2 (Fall-Winter 2020): 250–69.

51. ^ Suominen and Sivula, “Participatory Historians.”

52. ^ Shannon Mattern, “Maintenance and Care,” Places Journal, November 2018, 1–18, https://doi.org/10.22269/181120; and Russell and Vinsel, “After Innovation,” 1–25.

53. ^ See Niklas Nylund, Patrick Prax, and Olli Sotamaa, “Rethinking Game Heritage: Towards Reflexivity in Game Preservation,” International Journal of Heritage Studies 27, no. 3 (2021): 268–80, https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2020.1752772 .

54. ^ Mattern, “Maintenance and Care.”

Promille disk as it was found in the city forest. Originally posted by Pekka Kauranen on his Facebook profile, September 9, 2017 (Courtesy of the Finnish Museum of Games)